“Smoke and mirrors ”: An Assessment of the Commonwealth Government’s Voluntary Disinformation Code for Digital Platforms

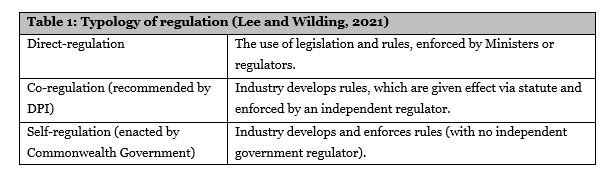

In November 2019, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) released the Digital Platforms Inquiry (DPI) final report (ACCC, 2019). Though its origins may have been accidental (Flew and Wilding, 2021), its’ 23 recommendations have proven far-reaching. Among other issues, the DPI report responded to particular concerns about misinformation and disinformation by recommending that the Commonwealth Government establish a co-regulatory model with and for the industry. In that model, industry, digital platforms, would develop a voluntary code (platforms sign-on) overseen and enforced by the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA).

This is not what occurred. Instead, the Commonwealth Government ordered that a voluntary code that would instead be self-overseen and self-enforced (Commonwealth Government of Australia, 2019). In response, DIGI, the industry representative for key digital platforms (including Facebook, Twitter and Google), established the Australian Code of Practice on Disinformation and Misinformation (the Code); taking effect in February 2021 (DIGI, 2021). The Code reflects what Gorwa (2019) notes is the increasing use of informal or and self-regulatory mechanisms amongst digital platforms. This brief examines the decision to delegate design and enforcement of the Code to the industry; in effect becoming self-regulation. It begins by explaining the key features of the policy and the Code, before moving to its risks and benefits, finishing with recommendations for future reviews and reform.

The Code

In response to the DPI recommendation, the Commonwealth Government opted to direct the industry to develop the Code, which would be self- rather than co-regulated. Under the Code, digital platforms may opt-in to the Code and can select which obligations apply to them, and, when they wish to withdraw (DIGI, 2021, p. 17). The Code sets out 6 objectives that signatories may sign onto, which are further operationalised into sub-outcomes, but rarely with required actions for compliance. More recently, DIGI has agreed with signatories to develop an informal complaints system. However, this system and its members cannot make binding decisions on digital platforms, and only adjudicates compliance with the Code, not actual instances of misinformation or disinformation (Sadler, 2021).

Benefits, risks and implementation challenges

The model has few benefits compared with several risks and weaknesses. Admittedly, there is a place for self-regulatory mechanisms, given they can utilise industry’s technical expertise (Windholz, 2017, pp. 161–162) and can reduce compliance costs for governments (Potoski and Prakash, 2005). The Code exemplifies this technical expertise in the many types of digital responses (e.g. labelling, down-ranking, signalling information sources) signalled that reflect contemporary best-practice (see similar recommendations: Kaye, 2019). However, as Faring and Sooriyakumaran (2021) note, the Commonwealth’s own guidance on regulation indicates that such self-regulation should only be done where risks and harms are minimal and there is an incentive for firms to comply (Australian Government, 2010, pp. 34–35), which does not reflect the conditions for regulating digital platforms.

The DPI clearly recommended a co-regulatory model, and a departure from this approach dramatically weakens enforcement measures. A lack of escalating enforcement measures granted to DIGI undermine its ability to secure compliance with the Code (see Ayres and Braithwaite, 1992; Parker and Nielsen, 2017). Indeed, as Gorwa (2019, p. 8) states, self-regulatory mechanisms may complement existing state-based regulation which serves as a baseline. This baseline is lacking. Instead, self-regulation may act as “smoke and mirrors” to distract from the need for more direct regulation (Hemphill and Banerjee, 2021).

Another key weakness of the model is the lack of reporting requirements. Reporting can form what Freiberg terms “informational regulation”, by providing transparency and incentivising good practice (see Freiberg, 2017, pp. 331–361). However the Code only has vague reporting requirements on the “outcomes”, but few on “actions” that could signify compliance (Wilding, 2021). Improved transparency has been called for by several civil society organisations and academics in response to the Code’s release (Farthing and Sooriyakumaran, 2021; Public Interest Journalism Initiative, 2021); particularly given the digital platforms’ operational secrecy (Marsden, 2017).

Another central failure of the self-regulatory approach is that it fails to engage with the business model that incentivises disinformation. Understanding a firm’s business model is crucial to securing compliance (Parker and Nielsen, 2017). In an attention economy (Wu, 2017), content that could constitute mis-information and dis-information often drives further engagement on platforms (Vosoughi, Roy and Aral, 2018), in turn driving greater advertising revenue (Lewandowsky et al., 2020). Therefore digital platforms have regularly distanced themselves from forceful content moderation due fear of driving users to other platforms (ACCC, 2019, pp. 189–195, 350). Consequently, as Lewandowsky et al. (2020, p. 5) state, ‘business models prevalent in today’s online economy constrain the solutions that are achievable without regulatory intervention.’

Future reviews and reforms

There are few reasons to be optimistic and many reasons to prepare for change. Erecting an immediate oversight mechanism is crucial. Parliamentary committees commonly support this (Freiberg, 2017, p. 86). The Commonwealth Parliament should establish a joint select and standing committee for the life of this Parliament and the next. These committees should require updates from industry on its compliance with the Code, involve civil society organisations, and report within 12 months of the 2022 Parliament’s establishment on whether the Code is fit-for-purpose. Given recent examples of electoral disinformation (Carson, Gibbons and Phillips, 2021), the 2022 federal election will provide a pressure-test for the Code’s effectiveness.

There are several reforms that should be considered in this report. The first is simply the execution of the co-regulatory model recommended by the DPI (ACCC, 2019). However, in order to do so, the Code may need to be sharpened with clearer actions and there would need to be legislative changes to enhance the ACMA’s mandate and powers to enforce a voluntary code (Wilding, 2021). The second should be how civil society can be more involved in the regulatory design and implementation process to guard against regulatory capture (see: Ayres and Braithwaite, 1992), which remains a concern regarding the ACMA (Muller, 2021).

Conclusion

The risk will be if self-regulation continues in its unaccountable form, it will, as occurs in other sectors (Williamson and Lynch-Wood, 2021, p. 30), will delay action on substantive regulation. In an era where misinformation and disinformation undermine democracy and risk public health, the costs of regulatory failure should be apparent.

References

ACCC (2019) Digital Platforms Inquiry: Final Report. Australian Competition and Consumer Commission.

Australian Government (2010) Best practice regulation handbook. Canberra.

Ayres, I. and Braithwaite, J. (1992) Responsive regulation: Transcending the deregulation debate. Oxford University Press, USA.

Carson, A., Gibbons, A. and Phillips, J.B. (2021) ‘Recursion theory and the “death tax” Investigating a fake news discourse in the 2019 Australian election’, Journal of Language and Politics, 20(5), pp. 696–718.

Commonwealth Government of Australia (2019) ‘Regulating in the Digital Age: Government Response and Implementation Roadmap for the Digital Platforms Inquiry’, Statement [Preprint].

DIGI (2021) Australian Code of Practice on Disinformation and Misinformation. Digi.

Farthing, R. and Sooriyakumaran, D. (2021) ‘Why the era of big tech self-regulation must end’, AQ-Australian Quarterly, 92(4), pp. 3–10.

Flew, T. and Wilding, D. (2021) ‘The turn to regulation in digital communication: the ACCC’s digital platforms inquiry and Australian media policy’, Media, Culture & Society, 43(1), pp. 48–65.

Freiberg, A. (2017) Regulation in Australia. Federation Press.

Gorwa, R. (2019) ‘The platform governance triangle: Conceptualising the informal regulation of online content’, Internet Policy Review, 8(2), pp. 1–22.

Hemphill, T.A. and Banerjee, S. (2021) ‘Facebook and self-regulation: Efficacious proposals–Or “smoke-and-mirrors”?’, Technology in Society, p. 101797.

Kaye, D. (2019) Speech police: The global struggle to govern the Internet. Columbia Global Reports.

Lee, K. and Wilding, D. (2021) ‘The case for reviewing broadcasting co-regulation’, Media International Australia, p. 1329878X211005524.

Lewandowsky, S. et al. (2020) ‘Technology and democracy: Understanding the influence of online technologies on political behaviour and decision-making’.

Marsden, C. (2017) ‘Prosumer law and network platform regulation: the long view towards creating offdata’, Geo. L. Tech. Rev., 2, p. 376.

Muller, D. (2021) ‘Where was the broadcasting regulator when Sky News Australia was airing misinformation about Covid-19?’, The Guardian, 8 July. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/aug/07/where-was-the-broadcasting-regulator-when-sky-news-australia-was-airing-misinformation-about-covid-19 (Accessed: 7 November 2021).

Parker, C. and Nielsen, V.L. (2017) ‘Compliance: 14 questions’, Regulatory theory: Foundations and applications, pp. 217–232.

Potoski, M. and Prakash, A. (2005) ‘Green clubs and voluntary governance: ISO 14001 and firms’ regulatory compliance’, American journal of political science, 49(2), pp. 235–248.

Public Interest Journalism Initiative (2021) ‘PIJI concerned by dis/misinformation code’, Public Interest Journalism Initiative, 22 February. Available at: https://piji.com.au/news/media-releases/piji-concerned-by-dis-misinformation-code/ (Accessed: 7 November 2021).

Sadler, D. (2021) ‘Big Tech misinformation efforts slammed as “woefully inadequate”’, InnovationAus, 11 October. Available at: https://www.innovationaus.com/big-tech-misinformation-efforts-slammed-as-woefully-inadequate/ (Accessed: 7 November 2021).

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D. and Aral, S. (2018) ‘The spread of true and false news online’, Science, 359(6380), pp. 1146–1151.

Wilding, D. (2021) ‘Regulating news and disinformation on digital platforms: Self-regulation or prevarication?’, Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy, 9(2), pp. 11–46.

Williamson, D. and Lynch-Wood, G. (2021) The Structure of Regulation: Explaining Why Regulation Succeeds and Fails. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Windholz, E. (2017) Governing through regulation: Public policy, regulation and the law. Taylor & Francis.

Wu, T. (2017) The attention merchants: The epic scramble to get inside our heads. Vintage.