The Regulatory Mandate for Victoria’s Forthcoming Regional Boards

When the Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System (Royal Commission) handed down its final report, it recommended a range of new and amended statutory agencies and departments to guide transformation.

The Victorian Collaborative Centre for Mental Health and Wellbeing would guide translational and interdisciplinary research, exemplifying among other things, lived experience-led initiatives.

The Mental Health Complaints Commission would become the Mental Health and Wellbeing Commission, with an enhanced powers, would drive systemic change an compliance with the Mental Health and Wellbeing Act 2022 (Vic).

A new Mental Health and Wellbeing Division inside the Department of Health would steward a system towards better outcomes.

There are successes, failures and uncertainties among these bodies.

One less discussed has been the role of the Regional Mental Health and Wellbeing Boards (Regional Boards), now in their embryonic form as Interim Regional Mental Health and Wellbeing Bodies (Regional Bodies). Established under Recommendation 4.2, the Regional Boards (after replacing their Bodies) will eventually be enabled to commission mental health services and hold individual providers accountable for outcomes and experiences of their services.

What may be less understood in the Victorian reform landscape, is that the Royal Commission clearly envisaged the Regional Boards as having a regulatory role. Identified as being necessarily separate from services to hold them accountable and best meet the needs of consumers, as well as families, carers and supporters,[1] the final report made clear that there would be clear commissioning and monitoring roles.[2]

Indeed, the Royal Commission made clear that the Regional Boards, along with the Department of Health, should be addressing quality and safety issues inside services. It spelled out steps such as:

‘directing the provider to develop a strategy to tackle the problem

linking the provider with an appropriate, complementary service to learn from their experiences and implement strategies to improve performance

having more direct intervention, such as engaging an independent expert to review policies and practices.’[3]

The final report went on to make clear that at it’s heart, this reflected a ‘responsive’ regulatory approach whereby Regional Boards will support services to meet standards, but intervene at crucial stages to improve performance.’[4]

In a system which continues to suffer a watchdog that refuses to bare its teeth, this role must be more crucially understood than ever. A conversation about the regulatory role of Regional Boards raises a series of questions and begs a great deal of work to begin today. Questions include:

What is regulation and what does it have to do with mental health and wellbeing services?

What kinds of tools would a Regional Board need to do its role?

What would ‘good’ regulation look like in Victoria’s mental health and wellbeing system?

What work should be underway to address this?

In the past few years, I've dedicated a lot of time to thinking about these topics. I worked at and advised the Mental Health Complaints Commission for four years. During this time, I wrote and co-wrote a number of academic papers[5] and interviewed leaders from Australia and around the world regarding workplace gender equality, human rights in prison, digital mental health technologies, Robo-Debt, and decisions made by the Victorian Supreme Court.[6]

If you want to learn about regulation, check out my previous podcast, From Rules to Reality: How Regulation Shapes, or Fails to Shape, Our Daily Lives.

It provides me with some starting points for these questions.

What is regulation and what does it have to do with mental health and wellbeing services?

Believe it or not, many people argue about what regulation really means. Some see it as strict rules made by bureaucrats, while others think it's just about what law allows and doesn’t allow. But this is too narrow in two ways.

First, it is wrong in scope: regulation is far closer to using a range of state-based (e.g. laws, taxes, accreditation, commissioning, transparency requirements) and community-based (e.g. exercising of rights, community pressure, freedom of information applications) tools to achieve an outcome in the public interest. A broader, and debatably too broad-a-definition, is that regulation is ‘steering the flow of events’[7] using the above and other tools.

The image or connection doesn't match the process, skills or complexities of regulation. Theories like responsive regulation or risk-based regulation help regulators handle the complexities of their roles. Regulatory oversight agencies operate knowing they can't monitor and enforce everything due to limited resources, unintended consequences of over-enforcement, and lack of visibility in some areas. Theories and skills of regulation deal with the complexity of achieving outcomes, such as compliance with human rights, requiring a specific set of skills.

In the context of Regional Boards, regulation or regulatory oversight could be provisionally understood as:

Utilising a range of powers including commissioning, compelling information and transparency mechanisms, providing enforceable written directions, as well as building and utilising community capital (power and expertise) get outcomes in new and existing mental health services that match the transformation agenda.

That transformation agenda is yet to be properly articulated, but will likely find its presence most clearly in the Mental Health and Wellbeing Performance and Outcomes Framework, the service standards already articulated in the Royal Commission, and the law (Mental Health and Wellbeing Act 2022 and the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006).

What kinds of tools would a Regional Board need to do its role?

Regulatory agencies need teeth to be able to effectively perform their role (whether they use them is another challenge). By the end of 2026, the Royal Commission projected that Regional Boards will have a range of powers to meeting their co-commissioning and regulatory oversight functions, without necessarily spelling them out. This will require legislative change to the Mental Health and Wellbeing Act 2022 (MHWA), which currently does not provide for either co-commissioning nor any powers.

A range of tools that may prove useful are detailed below.

Commissioning powers

These are projected and we should expect changes to the MHWA in the next 18 months to enable the Regional Boards to make unitary or co-commissioning decisions. Commissioning powers – using the big purse of public money derived from taxes – is an effective way to shape markets and/or achieve outcomes by setting conditions on the receipt of money.[8] The NDIS – which is under attack in the psychosocial disability space following the NDIS Review – had sought to radically reshape markets by putting the commissioning power in the hands of the participant. Commissioning powers in the Victorian public mental health service context, the Regional Boards can use commissioning powers to drive better improvement within current services, while also re-shaping the overall service-mix towards more rights-based, community-based and consumer-led mental health and wellbeing services.

Information and transparency powers

Commissioning alone isn’t enough to drive change, especially when some hospitals, like the banks in the US Financial Crisis, are ‘too big to fail’: there’s no immediately viable (or politically viable) alternative, at present, to fill the demand that these hospital currently respond to (often poorly).[9] Information and transparency powers are important in this respect.[10] The ability to compel information on service performance and to, where effective and appropriate, publish that information, will be crucial.

The recent court-case I am involved in with the Mental Health and Wellbeing Commission (Commission) provides a case-in-point that I have advocated for years on.[11] The release of service improvement recommendations made by the Commission has three important functions. First, it upholds the community’s right to know information about the services that impact them, and their right to information under section 15 of the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006. Second, it allows the community, such as consumers, carers, clinicians and advocates, to monitor whether those recommendations have been implemented in services – the Commission has limited visibility into services (it can’t go visit them daily), so extra sets of eyes are a value-add. Third, if those recommendations have been implemented, the community can assess whether the recommendations were effective or whether different recommendations are needed – an Aboriginal community in Warrnambool might view that recommendations weren’t sufficient to deal with culturally unsafe care/systemic racism, and that they want to collaborate to design better recommendations based on their expertise and community-connections. The use of information in this respect over the last nine years would have contributed to a better system than the one we currently inhabit.

Enforceable written directions

Regional Boards, to be able to effectively fulfill their mandate, will need powers to provide enforceable written directions to service providers. In the absence of the ability to do this, it is unclear how the Regional Boards will be able to ‘directing the provider to develop a strategy to tackle the problem’ or to intervene directly to require an external review.

The scope (what things can be directed on), reviewability (having court oversight) and rigmarole (steps the Regional Board needs to go through before it can give a direction) all need to be carefully designed, primarily between lived experience groups, services, Regional Boards and the Department of Health. An issue of overlap and complexity will need to be tackled, with the Commission, Chief Psychiatrist and Regional Boards all having somewhat duplicative powers. My view is that the Chief Psychiatrist’s powers haven’t been an effective tool for a decade, and that they should be removed[12] and the Regional Boards should occupy many of those powers going forward. This is something the sector should think about now rather than in 18 months’ time.

Community capital and the social licence

The best regulators act with the community behind them. A contrast can be drawn between the Commission and the Victorian Ombudsman. The Commission currently has extremely low satisfaction rates, with 24% and 26% of complainants (consumers/carers) saying that making a complaint created positive change for them or someone else (respectively). While there are no measures I have come across for the Victorian Ombudsman, my view is that it has, through important interventions such as the Housing Lockdown investigations and others, has far greater trust from the community. This is one of the reasons the Ombudsman was able to go to the media in 2022 to stop funding cuts: because the community values their services. The viability of the Regional Boards and their protection from cutting or legislative (having their powers trimmed) cuts will require that they are part of their community.

Part of this engages with issues around the social licence to operate. This states that distinct from the legal licence (authorised under the MHWA), Regional Boards, the Commission, and public mental health services must also consider their social licence to operate. Broadly speaking, social licence refers to the community’s acceptability and approval of an industry’s (e.g. mental health services’) operations. Regional Boards should engage with this ‘tool’ in two respects. First, they should be cognisant that through their actions, the community will be assessing whether they (Regional Boards) continue to have their social licence to operate – are they connected, trusted and seen as indispensable? Second, are they able to influence the social licence of mental health service providers, by re-shaping with the community, what they expect to be ‘morally good’ operations of mental health services in their community. Doing so interacts with powers to compel information to be a useful resource to them.

There’s much more to be said about this approach to regulation, including how the Regional Boards can enhance consumer-led regulatory efforts.[13] These conversations are best had over the next 12 months between Regional Bodies and their communities.

What would ‘good’ regulation look like in Victoria’s mental health and wellbeing system?

Regulation in mental health settings is distinct from regulating other areas, such as energy or pay inequity. Regulation in mental health settings must engage with the fact that the system never culturally or structurally deinstitutionalised: we still have continuing cultures of paternalism, we still have locked wards across the state (including decades-long admissions), and we still do so in a segregated fashion that doesn’t apply to people not labelled with a mental health issue.

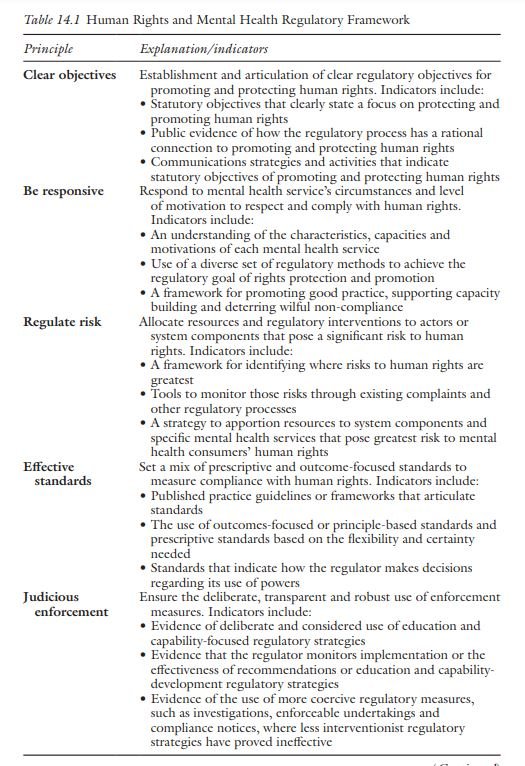

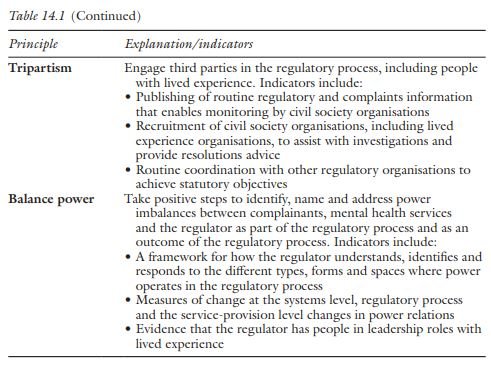

For that reason, and the underperformance of the Commission, Emeritus Professor Sharon Friel and I wrote the Human Rights and Mental Health Regulatory Framework.[14] The framework drew on responsive and risk-based regulatory theories, as well as theories of power, to develop principles and indicators for performance by the Commission. I draw out the table we developed below.

Unsurprisingly, we found the Mental Health Complaints Commission had performed poorly on most of these indicators, with some exceptions. The framework is designed less to assess the former Commission, and more to inform the current Commission and future regulators.

Though not a perfect-pair, these standards could well-inform how the Regional Boards go about their regulatory role. As noted, this regulatory role will need to be thought out: design of the tools, setting the indicators of good performance (like the above table), and then finding the skill sets to address this will be crucial.

What work should be underway to address this?

This blog is far from the final word nor my most complete or considered thinking on this issue. But I do hope Regional Bodies and the Department of Health are considering the regulatory role of Regional Boards and how to ensure that is a success. It will require engaging, more deeply, with the questions noted above. It will also require consideration of the skills-mix needed on Regional Boards and whether regulatory expertise is brought onto those Regional Boards (not my preferred approach).[15] Or, whether capability uplift and ongoing support should be provided to all Regional Bodies/Boards to enhance their regulatory knowledge and capabilities going forward (my preferred approach).

All of this, in my view, is what the Royal Commission asked for.

References

[1] State of Victoria, Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System, Volume 1: A New Approach to Mental Health and Wellbeing in Victoria (No Parliamentary Paper no. 202, Session 2018-2021 (document 2 of 6), State of Victoria, 2021) 269 <https://finalreport.rcvmhs.vic.gov.au/download-report/>.

[2] Ibid 270.

[3] State of Victoria, Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System, Volume 4: The Fundamentals for Enduring Reform (No Parliamentary Paper no. 202, Session 2018-2021 (document 5 of 6), State of Victoria, 2021) 154 <https://finalreport.rcvmhs.vic.gov.au/download-report/>.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Simon Katterl, ‘Regulatory Oversight, Mental Health and Human Rights’ (2021) 46(2) Alternative Law Journal 149; Simon Katterl, ‘The Importance of Motivational Postures to Mental Health Regulators: Lessons for Victoria’s Mental Health System in Reducing the Use of Force’ [2021] Australasian Psychiatry 10398562211038913; Simon Katterl, ‘Preventing and Responding to Harm: Restorative and Responsive Regulation in Victoria, Australia’ (2022) Early View Journal of Social Issues; Simon Katterl and Sharon Friel, ‘Regulating Rights: Developing a Human Rights and Mental Health Regulatory Framework’ in Kay Wilson, Yvette Maker and Piers Gooding (eds), The Future of Mental Health, Disability and Criminal Law (Routledge, 2023); Simon Katterl, ‘Resolving Mental Health Treatment Disputes in the Shadow of the Law: The Victorian Experience’ (2023) 2023(September) Australian Dispute Resolution Bulletin 20; Simon Katterl and Chris Maylea, ‘Keeping Human Rights in Mind: Embedding the Victorian Charter of Human Rights into the Public Mental Health System’ (2021) 27(1) Australian Journal of Human Rights 58.

[6] Simon Katterl, ‘Rules to Reality: How Regulation Shapes, or Fails to Shape, Our Daily Lives on Apple Podcasts’, Apple Podcasts <https://podcasts.apple.com/au/podcast/rules-to-reality-how-regulation-shapes-or-fails-to/id1582881485> (‘Rules to Reality’).

[7] John Braithwaite and Christine Parker, ‘Regulation’ in Peter Cane and Mark V Tushnet (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Legal Studies (Oxford University Press, 2003).

[8] Eric Windholz, Governing through Regulation: Public Policy, Regulation and the Law (Taylor & Francis, 2017) 173.

[9] We should, as part of deinstitutionalisation, be divesting money from these types of services to voluntary, community-based and consumer-led models and service types. If there is a role for hospital-based care (there are many other alternatives for crisis-based care), it should be far smaller than it currently is, and would bring the benefit of reduced costs. The Regional Bodies can do this if they identify that they want to, set targets shared targets and develop a pathway to get there.

[10] Arie Freiberg, Regulation in Australia (Federation Press, 2017) 331–361.

[11] Katterl, ‘Regulatory Oversight, Mental Health and Human Rights’ (n 5).

[12] Many of the quality and clinical governance functions that come under audits could be done without many of the powers currently in the Chief Psychiatrist, or simply move those functions to Safer Care Victoria. The Chief Psychiatrist can have a more limited role around Clinical Leadership in the sector.

[13] Simon Katterl, ‘Why Don’t We See Mental Health Consumers as Regulators? | LinkedIn’ <https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-dont-we-see-mental-health-consumers-regulators-simon-katterl/?trackingId=kq%2BYkAWoR8aWnX%2BtccjfRQ%3D%3D>.

[14] Katterl and Friel (n 5).

[15] Regulators from other industries who come into mental health often don’t show an understanding of the nuances of intersecting issues of human rights, power, institutionalisation, lived experience, professionalization and so on. It can lead to an overly technocratic approach to regulation, and not one that is “in” the community. At the very least, if people with regulatory expertise were brought on, they would need to have significant capability uplift in knowledge of these areas for their role to be most useful.